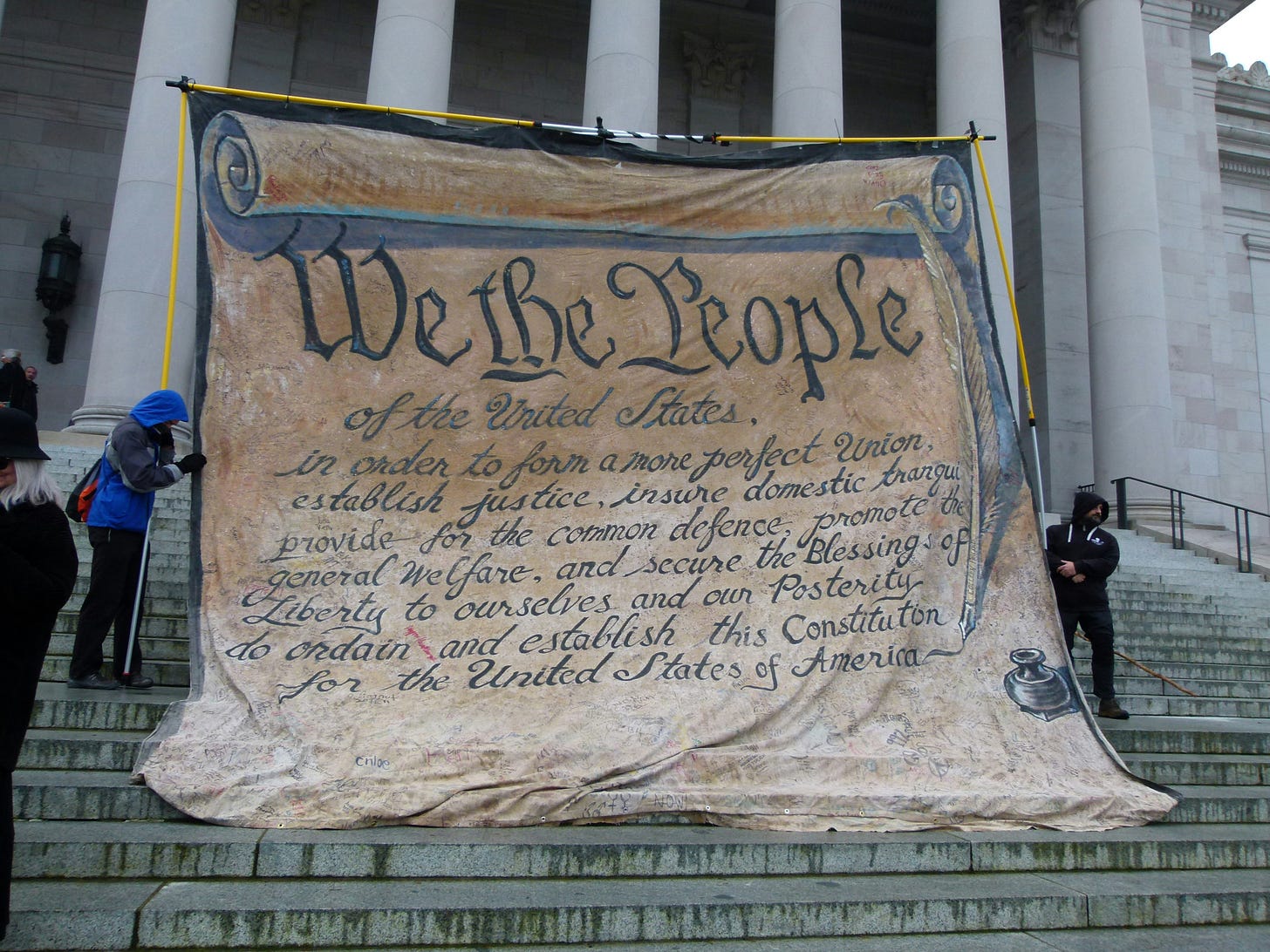

Banner No. 6 - The U.S. Constitution Must Be Amended

The framers intended constant improvement, not brittle rigidity

When the U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787, its authors did not imagine it as final, unchangeable scripture. They saw it as scaffolding—a framework, a living compact that would need adjustment as the nation grew. Article V, the amendment process, was no afterthought. It was the mechanism that made the Constitution adaptable instead of brittle.

But to really understand why the Framers insisted on an amendment process, we need to step back into their world and recall what came before.

Because the Constitution wasn’t America’s first attempt at self-government.

The Articles of Confederation: A Lesson in Rigidity

From 1781 to 1789, the young nation operated under the Articles of Confederation. The Articles reflected the Revolution’s deep suspicion of centralized authority, creating a “firm league of friendship” among sovereign states. But that league had cracks from the start:

No executive or judiciary. No president to enforce laws, no national courts to resolve disputes.

Weak Congress. It could not levy taxes, depending on voluntary contributions from states.

Unanimity required. Any amendment demanded all thirteen states’ approval—making reform essentially impossible.

Disunited commerce. States taxed each other, undermining economic stability.

Inadequate defense. The Confederation couldn’t fund a standing army or pay war debts. When Shays’ Rebellion erupted, it had no tools to respond.

George Washington, watching from Mount Vernon, captured the frustration:

“We are either a united people, or we are not. If we are, let us in all matters of general concern act as a nation… If we are not, let us no longer act a farce by pretending to it.”

The Constitutional Convention: A Bold Reset

By 1786, even cautious leaders admitted the system was broken. The Annapolis Convention pointed to the crisis, and Shays’ Rebellion made the danger undeniable.

When delegates met in Philadelphia in 1787, they were tasked with revising the Articles. Instead, they threw them out. Madison, Hamilton, and others argued for something new: a government strong enough to tax, defend, and regulate commerce—but constrained by checks and balances.

The result was the Constitution we recognize today, complete with:

A stronger executive (the presidency).

A national judiciary.

A bicameral Congress with clear powers to tax, regulate trade, and raise armies.

Crucially, an amendment process that required consensus but not unanimity.

The lesson was clear: rigidity strangles republics. The Framers had lived through the failure of a system too hard to fix. They designed a new one with built-in adaptability.

The Framers on Amendments

Madison, Jefferson, Hamilton, Franklin—each made the case for amendment in his own style:

Madison (1789):

“Let the Constitution have a fair trial; let it be examined by experience, discover by that test what its errors are, and then talk of amending.”

Jefferson:

“No society can make a perpetual constitution… Every constitution, then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years.”

Hamilton (Federalist No. 85):

Article V empowered both states and Congress to “originate the amendment of errors, as they may be pointed out by the experience.”

Franklin:

“I consent to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.”

They weren’t just open to change; they expected it. Amendment was a feature, not a flaw.

Ratification and the Bill of Rights

Even with these assurances, ratification was no slam dunk. Federalists argued the Constitution had enough safeguards. Anti-Federalists worried about tyranny without a bill of rights. The compromise? Federalists promised to add one immediately upon ratification.

That promise tipped the balance in key states. And Madison delivered: in 1789 he introduced amendments based on state constitutions and George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights. Ratified in 1791, they became the Bill of Rights—guaranteeing freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and due process.

Without that promise, the Constitution might not have been ratified at all. The Bill of Rights wasn’t a decoration; it was the price of admission, and the first proof that Article V worked.

George Washington, in his 1796 Farewell Address, gave advice still relevant today:

“If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment… But let there be no change by usurpation.”

In other words: use the tools of amendment. Don’t twist the Constitution for partisan ends.

For much of U.S. history, the amendment process was used steadily. Amendments abolished slavery, restructured presidential succession, established an income tax, granted women the right to vote, expanded civil rights, and lowered the voting age to 18.

Between 1789 and 1992, the Constitution was amended 27 times—roughly once every eight years. Change was normal. Necessary. Patriotic.

The idea that the Constitution should be frozen in amber is a recent invention. Since the 1970s, we’ve treated amendment as impossible, even dangerous.

That mindset is profoundly ahistorical.

The False Presumption of Permanence

Our present paralysis is not the Framers’ design. They gave us tools to adapt, but we’ve chosen not to use them. Schoolchildren are taught reverence without responsibility. Politicians tell us change equals chaos.

Meanwhile, new realities—digital privacy, reproductive freedom, climate change, corporate power, ubiquitous assault weapons, democratic representation—go unaddressed.

The Constitution isn’t failing because it’s weak. It’s failing because we refuse to use it as intended.

The Amendments We Need Now

To revive democracy, we must reclaim the amendment of the U.S. Constitution as a living practice. A starter slate of ten new amendments might include:

Equal Rights Amendment — gender equality guaranteed, finally.

Right to Vote — enshrined, uniform, and protected.

Birthright Citizenship — reaffirming that to be born here is to belong here.

Right to Privacy — from bodily autonomy to digital data.

Supreme Court Reform — expansion and term limits to restore balance.

Congressional Term Limits — breaking the cycle of career politicians.

Ban on Government Stock Trading — no government official should benefit from power by actively trading stocks or cryptocurrency.

Ban on Assault Weapons — weapons of war do not belong in the hands of civilians.

Expansion of the House — scaling representation to population.

National Referendum Process — letting citizens directly shape policy.

None of these ideas are radical. They’re pragmatic corrections—exactly what the Framers intended future generations to attempt. In future articles we will dig into these and explore other ideas for amending the Constitution and perfecting our union.

Reviving the Founders’ Spirit

Franklin’s humility, Jefferson’s radicalism, Madison’s pragmatism, Washington’s caution, Hamilton’s boldness—all pointed to one truth: the Constitution was never meant to be sacred scripture.

It was meant to breathe. It was meant to grow.

If we want the American experiment to endure, we can’t just preserve it like a museum piece.

We have to amend it. That’s not betrayal—it’s fidelity.

The Framers trusted us with the tools.

The question is whether we’ll have the courage to use them.

Understanding our history is a way to better understand our current times. Read about the vitriol and harsh campaigning to ratify the Constitution in Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 by Pauline Maier.

I agree the Constitution was created with the idea to be Amended over time as the country grows and the needs of the people change.

This framers constructed a "living document" thus like a baby transitions and grows into a toddler then adolescent then preteen so on ans so forth.

As the country grows and the nation embarks in its struggles and progress its the hope and intent that the gov't, the nation, the society will improve.